Up and Down California in 1860-1864

The Journal of William H. Brewer: Book 5, Chapter 3 – OWENS VALLEY AND THE SAN JOAQUIN SIERRA

The Prospectors’ Trail—Kearsarge Pass—Owens Valley—Desert Characteristics—Incidents of Inyo—Indian Signals—A High Pass—The Upper San Joaquin—Attempt to Reach Mount Goddard—Newspapers in Camp—Canyons of the San Joaquin—Hoffmann Seriously Ill—Pushing On to Clark’s Ranch—To Yosemite with Mr. Olmsted—Notice of Professorship at Yale.

Camp 189, on the middle fork of the San Joaquin.

August 5, 1864.

I wrote last on July 23, while the boys were exploring for a way to get north. They were unsuccessful, and I decided to cross the summit to Owens Valley.

Sunday, July 24, we remained in camp for latitude observations, but the forenoon was cloudy and the afternoon rainy—heavy showers. In keeping instruments dry I got my blankets wet, and although it cleared up at evening, I had a rheumatic night in my wet blankets. There were slight showers during the night, but no heavy rain, and the next morning was clear. We packed up, got back into the canyon by our steep trail, killed a tremendous rattlesnake on the way, and camped again at the head of the valley, where we had been a week before. One of the soldiers caught a fine mess of trout. We have seen deer in abundance, but have not succeeded in getting any lately.

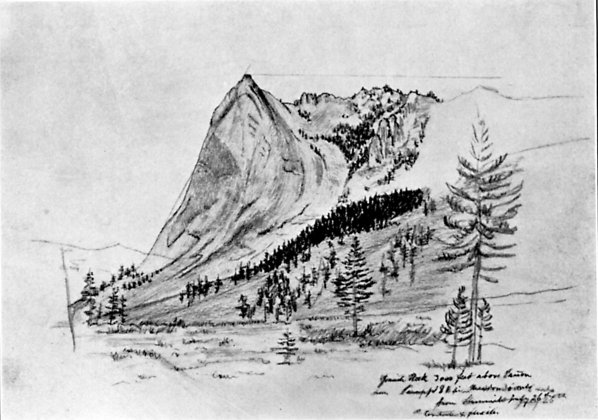

Some prospectors had come over the summit to this place, as I told you, and we resolved to follow their trail, assuming that where they went we could go. Tuesday, July 26, we started and got about eleven miles, a hard day’s work, for we rose 4,300 feet. First we went up a steep, rocky slope of 1,000 to 1,500 feet, so steep and rough that we would never have attempted it had not the prospectors already been over it and made a trail in the worst places—it was terrible. In places the mules could scarcely get a foothold where a canyon yawned hundreds of feet below; in places it was so steep that we had to pull the pack animals up by main strength. They show an amount of sagacity in such places almost incredible. Once Nell fell on a smooth rock, but Dick caught her rope and held her—she might have gone into the canyon below and, with her pack, been irretrievably lost. We then followed up the canyon three or four miles and then out by a side canyon still steeper. We camped by a little meadow, at over nine thousand feet. Near camp a grand smooth granite rock rose about three thousand feet, smooth and bare.1

July 27 we went over the summit, about twelve miles. The summit is a very sharp granite ridge, with loose boulders on both sides as steep as they will lie. It is slow, hard work getting animals over such a sliding mass. It is 11,600 feet high, far above trees, barren granite mountains all around, with patches of snow, some of which were some distance below us—the whole scene was one of sublime desolation. Before us, and far beneath us lay Owens Valley, the desert Inyo Mountains beyond, dry and forbidding. Around us on both sides were mountains fourteen thousand feet high, beneath us deep canyons.2

We descended down the canyon of Little Pine Creek3 and camped at a little meadow, in full view of the valley below and the ridges beyond, which were peculiarly illumined by the setting sun. On both sides of us were great rocky precipices. During the day’s progress we passed a number of beautiful little lakes.

Thursday, July 28, we were up at dawn and went to Owens River, sixteen miles. Six miles brought us out of the canyon on the desert—then ten miles across the plain in the intense heat,

MOUNT WHITNEY, IN DISTANCE AS SEEN FROM THE SLOPE OF MOUNT BREWER From a photograph by Ansel F. Hall |

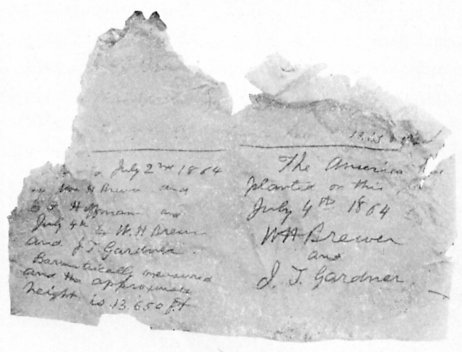

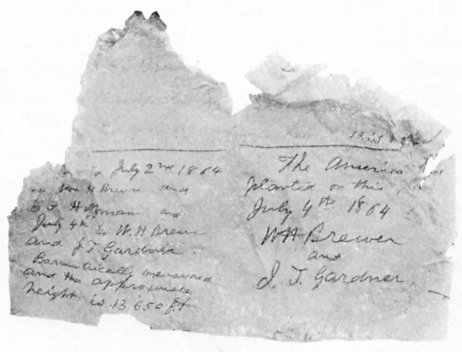

RECORD FOUND ON THE SUMMIT OF MOUNT BREWER IN 1896 |

and we camped on the river bank, without shade or shelter, the thermometer 96° in the shade, 156° in the sun. Yesterday in the snow and ice—today in this heat! It nearly used us up.

Owens Valley is over a hundred miles long and from ten to fifteen wide. It lies four thousand to five thousand feet above the sea and is entirely closed in by mountains. On the west the Sierra Nevada rises to over fourteen thousand feet; on the east the Inyo Mountains to twelve thousand or thirteen thousand feet. The Owens River is fed by streams from the Sierra Nevada, runs through a crooked channel through this valley, and empties into Owens Lake twenty-five miles below our camp. This lake is of the color of coffee, has no outlet, and is a nearly saturated solution of salt and alkali.

The Sierra Nevada catches all the rains and clouds from the west—to the east are deserts—so, of course, this valley sees but little rain, but where streams come down from the Sierra they spread out and great meadows of green grass occur. Tens of thousands of the starving cattle of the state have been driven in here this year, and there is feed for twice as many more. Yet these meadows comprise not over one-tenth of the valley—the rest is desert. At the base of the mountains, on either side, the land slopes gradually up as if to meet them. This slope is desert, sand, covered with boulders, and supporting a growth of desert shrubs.

Here is a fact that you cannot realize. The Californian deserts are clothed in vegetation—peculiar shrubs, which grow one to five feet high, belonging to several genera, but known under the common names of “sagebrush” and “greasewood.” They have but little foliage, and that of a yellowish gray; the wood is brittle, thorny, and so destitute of sap that it burns as readily as other wood does when dry. Every few years there is a wet winter, when the land of even these deserts gets soaked. Then these bushes grow. When it dries they cease to put forth much fresh foliage or add much new wood, but they do not die—their vitality seems suspended. A drought of several years may elapse, and when, at last, the rains come, they revive into life again! Marvels of vegetation, some of these species will stand a tropical heat and a winter’s frosts; the drought of years does not kill them, and yet the land may be flooded and be for two months a swamp, and still they do not die. Such for instance is the common sagebrush of the deserts, Artemisia tridentata.

The aspect of these deserts is peculiar. In the distance, when individual bushes cannot be distinguished, they look like a gray plain of uncovered soil; near by they are still gray, or yellowish gray, but covered with bushes—no grass, few herbs, and no trees, only half a dozen species of bushes.

The Inyo Mountains skirt this valley on the east. They, too, are desert. A little rain falls on them in winter, but too little to support much vegetation or to give birth to springs or streams. They look utterly bare and desolate, but they are covered with scattered trees of the little scrubby nut pine, Pinus fremontiana,4 and some other desert shrubs, but no timber, nor meadows, nor green herbage. There are a few springs, however. These mountains were the strongholds of the Indians during the hostilities of a year ago. They are destitute of feed, and the water is so scarce and in such obscure places that the soldiers could not penetrate them without great suffering for want of water. Camp Independence was located in the valley, and for a year fighting went on, when at last the Indians were conquered—more were starved out than killed. They came in, made treaties, and became peaceful. One chief, however, Joaquin Jim, never gave up. He retreated into the Sierra with a small band, but he has attempted no hostilities since last fall. These Indians are in the region where we are now, and it was against them that we took the escort of soldiers as a guard. There are a number yet, however, in the valley, living as they can—a miserable, cruel, treacherous set.

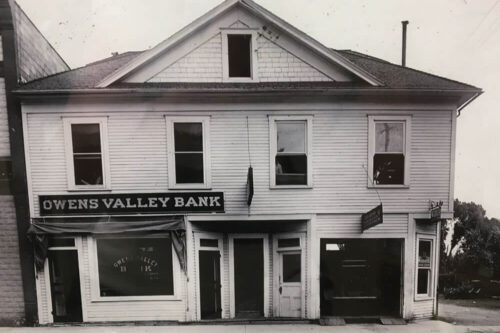

Mines of silver and gold were discovered in the Inyo Mountains some two or three years ago. They made some excitement, a few mills were erected, and three villages started—Owensville, San Carlos, and Bend City. The last two are rivals, being only 2 1/2 miles apart; the first is 50 miles up the river. We camped on the river near Bend City and went into town for fresh meat and to get horses shod. It is a miserable hole, of perhaps twenty or twenty-five adobe houses, built on the sand in the midst of the sagebrush, but there is a large city laid out—on paper. It was intensely hot, there appeared to be nothing done, times dull, and everybody talking about the probable uprising of the Indians—some thought that mischief was brewing, others not.

Friday, July 29, we were up at dawn and started up the valley, and traveled twenty-two miles, about three-fourths of the way over deserts, the rest over grassy meadows. Many settlers have come in with cattle this year. Most of them are Secessionists from the southern part of the state. We passed the old Camp Independence, so lively a year ago—now a ranch, and the adobe buildings falling into ruin.

It was a terrible day. The thermometer ranged from 102° to 106°, often the latter, and most of the time 104°. It almost made us sick. There was some wind, but with that temperature it felt as if it came from a furnace. It came from behind us and blew the fine alkaline dust into our nostrils, making it still worse. We camped by the river and took a cooling bath. Our camp was the scene of a fearful tragedy a year ago. The Indians attacked a party of one man, a nigger, two women, and a child. The nigger was on horseback and fought well, killing several. In attempting to cross the river the team horses were drowned. He gave his horse to the women—both of whom got on it, and they and the white man escaped to Camp Independence. The Indians caught the negro and afterward said that he was tortured for three days.5

During this day’s ride the Sierra loomed up grandly. The crest is at the extreme eastern part of the chain—grand rocky peaks, some of them over fourteen thousand feet, their cool snow, often apparently not over ten miles from us, mocking our heat.

Saturday, July 30, we kept on our way up the valley. It was not so hot—100° to 104°, most of the time 101°. We had the same features—deserts most of the way, grassy meadows where streams came down from the Sierra and spread on the plain, the barren Sierra on the west, the more barren Inyo Mountains on the east. The eastern slope of the Sierra is here almost destitute of trees, save in the canyons and along the streams.

We camped by a creek, where also a stream of warm water comes from some copious hot springs about a mile distant. We took a luxurious bath. Although the stream of cold water was abundant, it dried up in the intense heat before night and ceased to run, but flowed again the next morning. We have seen Indians along up the valley, but they shunned us, afraid of the soldiers. One only came into camp. There was a sweat house and other Indian “fixens” near camp, but the Indians all kept away.

We wanted some fresh meat, so two of the boys went out and shot a fine heifer and brought in the beef. They assumed that she belonged to a Secessionist and confiscated her. It is very common here for men traveling to supply themselves with beef from the large herds, but this is the first time that we have ever done it—in fact, it was the soldiers who did it, but we helped eat the beef, and it answered us a very good turn indeed.

At our camps in the valley our only fuel was sagebrush, which burns like tinder, but is little better than straw to cook by. No trees grow in the valley.

Sunday, July 31, we were up very early, but not refreshed, for the mosquitoes had allowed us but little sleep. We went up the valley sixteen or seventeen miles where a lava table crosses the entire valley, barren in the extreme. Here a stream comes down, and there is a sort of basin where there are nine or ten square miles of the best grass I have seen in the state. Three or four settlers have come in this year with cattle and horses, but there is feed for ten times as many. One has started a garden, to sell vegetables in Owensville, ten or fifteen miles distant, and Aurora, sixty-five miles distant. He came into camp and wanted to sell vegetables. I bought some, also four pounds of butter—all luxuries. Perhaps you would be interested to know what prices are asked for vegetables so far from any market. They were: green peas in the pod, ten cents a pound; turnips, eight cents a pound; cucumbers, twenty-five cents a dozen; radishes, thirteen cents a dozen; butter, seventy-five cents a pound, in gold—now worth three times its face in greenbacks. But they were very acceptable notwithstanding their price.

Monday morning, August 1, we were up early. Some of the horses strayed away and two hours were spent in finding them, so we got a late start. We struck into the mountains by a blind Indian trail. Last year some soldiers were piloted over the summit by friendly Indians, in pursuit of hostile ones, by this trail. One of them was with us and knew the way. Our way was continually up and we had grand views of the desert plain below and the desert mountains beyond. The Sierra lay ahead, with high peaks and cool snows.

We camped in the canyon of the southwest fork of Owens River at over eight thousand feet. As soon as we halted signal smokes rose from the hills around, and after dark signal fires blazed, the Indians telegraphing our progress. The fires were bright, but short. Ice formed that night, a pleasant change from the heat of the last few days.

August 2 we were off in good season. As soon as we started the signal smokes again showed that we were watched. I will not repeat, but let it suffice to say that all of our movements up to the present time have been thus telegraphed. As soon as we stop, smokes rise, when we start they appear, and at night their blaze is seen on the heights—so the Indians know all of our movements.

We crossed the summit that day. As we approached it, it seemed impassable—great banks of snow, above which rose great walls and precipices of granite—but a little side canyon, invisible from the front, let us through. The pass is very high, nearly or quite twelve thousand feet on the summit. The horses cross over the snow. So far as I know it is the highest pass crossed by horses in North America. There is no regular trail, but Indians had taken horses over it before the soldiers did. The region about the pass is desolate in the extreme—snow and rock, or granite sand, constitute the landscape.6

We came down a very steep slope 2,500 feet and camped on the middle fork of the San Joaquin, near its head. The next day we climbed a ridge south, to see the country, and had a grand view, but as it is so similar to those already described I will give no description. We met eleven Indians, all well armed with rifles, but they avoided us. Their signals blazed, however, until near midnight.

August 4, yesterday, we came down the valley to this camp, eighteen miles. In places the canyon widens into a broad valley. There are many beautiful spots, but they have been rarely seen by white men before.7 It is the stronghold of Indians; they are seldom molested here, and here they come when hunted out of the valleys. We saw their signs everywhere; their fires and smokes on the cliffs near showed their presence, but we saw not a man, woman, or child. Once we came on a camp fire still burning, but the Indians were out of sight.

In this valley hundreds of pine trees have the earth dug around them to protect them from fire, for pine seeds or nuts form an important article of food with the Indians. One species has very large cones, with large seeds—hundreds of bushels of seeds are gathered for food.

This morning four soldiers left for Fort Miller for supplies. They took an unknown way, following the foot trail, but hope to be back in seven days, while we will work south into the region we could not penetrate from Kings River. I have stopped here today to wash clothes, mend, write up my notes, etc., for we have been on the go incessantly for the last eleven days.

Middle fork of the San Joaquin.

August 14.

We are again back here, stopping over a day, and I will go on with my story. And yet I have a mind to pass it over, it is so like the rest. Rides over almost impassable ways, cold nights, clear skies, rocks, high summits, grand views, laborious days, and finally, short provisions—the same old story.

Yet one item is worth relating. A very high peak, over thirteen thousand feet, rises between the San Joaquin and Kings rivers, which we call Mount Goddard, after an old surveyor in this state. It was very desirable to get on this, as it commands a wide view, and from it we could get the topography of a large region. Toward it we worked, over rocks and ridges, through canyons, and by hard ways. We got as far as horses could go on the ninth, and thought that we were within about seven miles of the peak.

We camped at about ten thousand feet, and the next day four of us started for it—Hoffmann, Dick, Spratt (a soldier), and I. We anticipated a very heavy day’s work, so we started at dawn. We crossed six high granite ridges, all rough, sharp, and rocky, and rising to over eleven thousand feet. We surmounted the seventh, a ridge very sharp and about twelve thousand feet, only to find the mountain still at least six miles farther, and two more deep canyons to cross. We had walked and climbed hard for nine hours incessantly, and had come perhaps twelve or fourteen miles. It was two o’clock in the afternoon. Hoffmann and I resigned the intention of reaching it, for it was too far and we were too tired.

Dick and Spratt resolved to try it. We did not think they could accomplish it. Dick took the barometer and I took their baggage, a field glass, canteen, and Spratt’s carbine, which he had brought along for bears. Hoffmann and I got on a higher ridge for bearings, and then started back and walked until long after sunset—but the moon was light—over rocks. We got down to about eleven thousand feet, where stunted pines begin to grow in the scanty soil and crevices of the rocks. We found a dry stump that had been moved by some avalanche on a smooth slope of naked granite. We stopped there and fired it, and camped for the night.

We had brought along a lunch, expecting to be gone but the day. It consisted of dry bread and drier jerked beef, the latter as dry and hard as a chip, literally. This we had divided into three portions, for three meals, a mere morsel for each. This scanty supper we ate, then went to sleep. The stump burned all night and kept us partially warm, yet the night was not a comfortable one. Excessive fatigue, the hard naked rock to lie on—not a luxurious bed—hunger, no blankets—although it froze all about us—the anxieties for the others who had gone on and were now out, formed the hard side of the picture.

But it was a picturesque scene after all. Around us, in the immediate vicinity, were rough boulders and naked rock, with here and there a stunted bushy pine. A few rods below us lay two clear, placid lakes, reflecting the stars. The intensely clear sky, dark blue, very dark at this height; the light stars that lose part of their twinkle at this height; the deep stillness that reigned; the barren granite cliffs that rose sharp against the night sky, far above us, rugged, ill-defined; the brilliant shooting stars, of which we saw many; the solitude of the scene—all joined to produce a deep impression on the mind, which rose above the discomforts.

Early in the evening, at times, I shouted with all my strength, that Dick and Spratt might hear us and not get lost. The echoes were grand, from the cliffs on either side, softening and coming back fainter as well as softer from the distance and finally dying away after a comparatively long time. At length, even here, sleep, “tired nature’s sweet restorer,” came on. Notwithstanding the hard conditions, we were more refreshed than you would believe. After months of this rough life, sleeping only on the ground, in the open air, the rocky bed is not so hard in reality as it sounds when told. We actually lay “in bed” until after sunrise, waiting for Dick. They did not come; so, after our meager breakfast we started and reached camp in about nine hours. This was the hardest part. Still tired from yesterday’s exertions, weak for want of food, in this light air, it was a hard walk.

At three in the afternoon we reached camp, tired, footsore, weak, hungry. Dick had been back already over an hour, but Spratt had given out. Gardner and two soldiers, supposing that Hoffmann and I also had given out, had started with some bread to look for us. We shot off guns, and near night they came in, and at the same time Spratt straggled into camp, looking as if he had had a hard time. Dick and he did not reach the top, but got within three hundred feet of it. They traveled all night and had no food—they had eaten their lunch all up at once. Dick is very tough. He had walked thirty-two hours and had been twenty-six entirely without food; yet, on the return, he had walked in four hours what had taken Hoffmann and me eight to do.

Supper and sleep partially restored us, but we came back here the next day, a long, hard day’s work. This was necessary, for we were out of flour, rice, beans—in fact, had only tea, sugar, and bacon. This was to be our rendezvous with the soldiers, and they had got in only an hour ahead of us, with an abundance of provisions. Not a great variety, but an abundance of salt pork, flour, coffee, and sugar, so we are all right again.

I have stopped here two days, Saturday and Sunday, to rest, wash, and mend clothes, and write up notes.

The soldiers brought back a lot of newspapers from the camp at Fort Miller—papers from the East, from various parts of this state—old many of them, but very acceptable. Yesterday, after washing my clothes, I spent the rest of the day in reading. There is a sort of fascination in reading about what is going on in the busy world without, in the noisy marts of trade and commerce, in society and politics, in the busy strife of war, of brilliant parties and gay festivities, and sad battles, and tumultuous debate, while we are here in these distant mountain solitude, alike away from the society and the strife of the world.

Camp 195, near north fork of the San Joaquin.

August 18.

Monday, August 15, we packed up and started and made a big day’s march toward the north fork.8 We had rather rough going and finished by going down a steep hill about two thousand feet. The north fork runs in a very deep, rocky canyon still a thousand feet deeper. We camped at good grass, but poor water—some pools that remained in a little swamp. Near our camp the canyon is very grand—a notch in the naked granite rocks. During the day we crossed a number of streams bordered by dense thickets of alders through which we had to cut our way with our knives. In one of these, Buckskin, our pack horse, caught a leg between two rocks and bruised it badly.

The next morning we were off as usual, but soon found that we were “in a fix”—great granite precipices descended ahead of us. We turned back, and after much trouble found a very steep, rocky place where we could get down about one thousand feet to the river. Buckskin was so lame that I camped before noon, at the river, after going only about four miles. It was a lovely spot—a little flat of a few acres, with grand old trees, and high, naked granite cliffs around. The river runs through this, entering and leaving it by an impassable canyon. We found the river full of trout, and the boys caught a fine mess.

San Francisco.

October 12.

Two months have passed since I have written anything about our trip, and I must now resume the story to make it complete. I was just telling about getting into the canyon of the north fork of the San Joaquin River. One of the soldiers, Win Orr, was ahead. We tried to stop him but could not. The upshot of the matter was that he got lost, and we heard nothing of him for many days. He gave us much trouble. During the day a deaf and dumb Indian came into camp. It was remarkable to see how he would express what he had to say by his actions and pantomime.

August 17 we started again, putting the pack on another animal. We had a tremendous climb to begin with. First a very heavy hill, three thousand feet high, and just as steep as animals can climb. We struck the trail of Orr, the lost soldier, but we soon came to a region where there were cattle, and their abundant tracks prevented us from seeing which way he went, so we camped, and I sent out two soldiers to look for him. The search was continued for the next day. They found his tracks in places, but there were Indian tracks also and we feared that they had got him.9

We had a grand view from the hill we crossed. The peaks along the summit are very black and desolate, and with much snow, and the canyons very deep and abrupt. We found cattle in the woods, and the soldiers shot a beef and we had fresh meat again, a true luxury. We then worked west one day, and then another was spent in getting the topography of the region. I was not at all well and lay in camp one day, miserable enough.

For a week or ten days Hoffmann had been complaining of a sore spot on one of his legs, but nothing could be seen to indicate any hurt or injury. He came back from a trip away from the camp so lame that he could scarcely walk. I resolved to push out. I was getting run down, felt nearly sick, our provisions were low, and Hoffmann was getting rapidly worse. So the next morning, August 21, Sunday, we started.

We had a terribly rough way at first, but finally struck some cattle trails, and, at length, the first dawn of returning civilization. We found two men camped under a tree, watching cattle which they had driven up from the plains. We rode twenty-three miles and then camped at the altitude of about eight thousand feet. Hoffmann had grown so much worse that by night he had to be lifted from his horse and could not walk a step. It had been cloudy all day, and soon after dark a cold rain set in and it rained hard all night. There is no need of again describing the discomforts and miseries of sleeping on the ground in a cold, rainy night, when the rheumatism creeps into every nook and joint of one’s frame. It was hard on poor Hoffmann. It is bad enough for a well man, but for a sick man, racked with pain, tired from the day’s riding, feeble, weak, and used up, it is hard, indeed.

The next day it rained but little, but he got steadily worse. We had to lift him on and off his horse and travel on the slowest walk. We had trails most of the day, however. We passed several cabins, in some of which white men were living with squaws, and lots of half-breed “pledges of affection” were seen. We descended rapidly and camped in the valley of the Fresno River, five thousand feet lower than the place we started from in the morning. We stopped at a ranch and got some potatoes and green corn. Ah, what real luxuries they seemed! The proprietor had a squaw wife and a growing family. It is a noteworthy fact that nearly all the “squaw men” (men living with squaws) in this state are rank Secessionists—in fact, I have never met a Union man living in that way. They are generally the “poor white trash” from the frontier slave states, Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas.

The night was very hot, the air steamy, for it rained some, and Hoffmann grew worse—his leg was very painful. The next day, August 23, we got to Clark’s Ranch, on the Yosemite trail.10 Hoffmann was in a bad state; indeed, we could scarcely get him so far.

This looked like civilization. We met Mr. and Mrs. Ashburner, Mr. Olmsted,11 and other friends, who had been at Yosemite. You can imagine the joyous meeting. We were a hard-looking set—ragged, clothes patched with old flour bags, poor—I had lost over thirty pounds—horses poor. We camped there and hoped for Hoffmann to recruit. There he remained three weeks from that time, some of us with him all the time, but he grew no better, in fact, rather worse. After stopping there three days I went to Yosemite Valley with Mr. Olmsted. He is the manager of the Mariposa Estate. His family were in the valley, where they spend several weeks during the heat of the summer.

The great Yosemite is ever grand, but it was less beautiful than when I saw it before. The season has been so very dry that the grassy meadows at the bottom were brown and sere, the air hazy, the water low. Over the great Yosemite Fall but a mere rill trickled, so small that it was entirely dispersed by the wind long before it reached the bottom of its great leap of half a mile.

We took a week and went back to the summit on the Mono trail, where we had such a pleasant time last year. It was a charming trip. I threw off the anxiety that had weighed me down of late, and enjoyed the scenery of that grand region. Mr. Olmsted is a very genial companion and I enjoyed it.12

I got back to Clark’s Ranch September 6 and found Hoffmann no better. He was anxious to get where he could get medical advice. We tried to get Chinamen to carry him to Mariposa, for we were twelve miles from a wagon road. At last, September 10, we four started to carry him ourselves. We made a litter and put a bed on it and started. The trail was so narrow that only two could carry at once. The trail led over a hill over six thousand feet high, and he grew heavier and heavier mile by mile, but it was successful. Gardner and I returned for our animals, while King and Dick went on, and we all met again at Mariposa. There we got a carriage, put a bed in it, and King and Dick got him to Stockton, a hundred miles distant, and thence by steamer to San Francisco. He is still very sick and may never recover.

Gardner and I spent a few days on the Mariposa Estate, looking at its mines and mills, but I will give no description. It is a tremendous estate. I rode to Stockton with Mr. Olmsted in his private carriage, carrying $28,000 in gold bullion—quite a load.

I have received unofficial notice of my election as professor at Yale, and shall be on the road in a week if I can. I am now working hard to get off early, but will not close my journal yet, for a long trip still lies before me. I have counted up my traveling in the state. It amounts to: horseback, 7,564 miles; on foot, 3,101 miles; public conveyance, 4,440 miles—total, 15,105 miles. Surely a long trail!

CLIFF NEAR CAMP 181 ON CHARLOTTE CREEK HEADWATERS OF KINGS RIVER From a sketch by Charles F. Hoffmann |

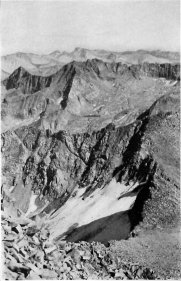

CANYON OF THE UPPER SAN JOAQUIN RIVER From a sketch by Charles F. Hoffmann |

NOTES

1. The route was up Bubbs Creek (named for John Bubbs, one of the prospectors) and up Charlotte Creek.

3. Now called Independence Creek.

4. Usually classified as Pinus monophylla Torrey; also called one-leaf piñon.

5. A circumstantial account of this episode is told by W. A. Chalfant, The Story of Inyo (Bishop, California, 1922), pp. 136-138.

6. This was Mono Pass, leading from the head of Rock Creek (the southwest fork of Owens River) to Mono Creek (called by Brewer the middle fork of the San Joaquin). The name Mono is that of a widely scattered division of Shoshonean Indians and is found in many localities throughout the Sierra. This pass is not to be confused with the one farther north at the head of the Tuolumne.

7. For thirty years after Brewer’s visit this region continued to be practically unknown save to Indians and sheepherders. In 1894 Theodore S. Solomons explored it and named some of its features, including the broad valley (Vermilion Valley) (Sierra Club Bulletin, Vol. I, No. 6 [May, 1895]).

8. This is now known as Middle Fork; there is a branch coming into it farther up now called North Fork.

9. Brewer’s notebook states that on August 21 they learned that Orr had passed through the cattle camp safely several days before.

11. Frederick Law Olmsted, famous landscape architect, was in California in 1863-64 as superintendent of the Mariposa Estate, the huge mining property of which Frémont, once the sole owner, was at this time losing control.

12. In the notebook there is an account of a climb of Mount Gibbs with Mr. Olmsted, of which the following is an abridgment: “August 31, started [from camp at Mono Pass] for the summit, but took the next peak south of Mount Dana, fearing Olmsted could not reach the other. On this peak I managed to get his horse up, so we rode to the top. He named the peak Mount Gibbs, after O. W. Gibbs [Oliver Wolcott Gibbs, Professor of Science at Harvard]. Strange enough we saw a group of persons on Mount Dana, clear against the sky. These turned out to be the party of a Mr. St. Johns, including a little girl six years old and a man sixty-two years old and lame. We met them at the Soda Spring next day.”

Written by:

Guest Blogger

Our guest bloggers come from various locations and walks of life, but all share a common interest in this beautiful place.