Trail Running California’s 14ers

“Run ‘N Bag” in the Eastern Sierra

By: Jeff Kozak

Back in 2013, I found myself in a chance conversation with rock climbing legend, Alex Honnold, when he stopped by the outdoor gear shop where I was working in Bishop, California. He was in the area reconning an upcoming human-powered mission with Cedar Wright—another contemporary stone master— to climb all of California’s 14’ers while cycling and/or hiking between each access point. It was a true enduro sufferfest that would make any ultrarunner proud.

The duo still had not decided on their route up the Sierra’s southernmost 14’er, Mt. Langley. Before my mind could get in front of my mouth to put the brakes on an embarrassing foot insertion, my irrepressible inner trail runner blurted out:

“There’s sweet singletrack most of the way to the summit from the south.”

What followed was the most pregnant of faux pauses, followed by a friendly smirk.

“Ahhh, we’ll probably do one of the more, uh, technical routes on the north face.”

My naïve gaff notwithstanding, the truth is that the apex intersection of pure trail running, technical rock climbing and the scrambly off-trail terrain that connects the two disciplines, lies on the summits of lofty, and sometimes remote, alpine peaks. The main limiting factors on potential objectives are one’s endurance and degree of technical alpine skill (which encompasses both rock and mixed – snow and ice – terrain) combined with comfort level on varying gradations (third class through fifth class) of exposed terrain. Possess all the attributes in spades and you have the potential to become some version of Kilian Jornet, transforming some of the world’s most intimidating mountains into your personal playground.

For the rest of us, there’s the Sierra and its lofty basin and range companion framing the east side of the Owens Valley – the White Mountains. The Sierra, with its steep eastern escarpment, gentle west slope, infrequent summer monsoon and Mediterranean climate, is a mountain running paradise for all degrees of skill and ambition. The vast majority of peaks have both technical and non-technical routes to reach their high points, opening the door to all manners of summit style.

Many years ago, a friend referred to the contagious combination of trail running and peak bagging as “run ‘n bag.” Whether it was his coin or not, the phrase held perfectly descriptive – if occasionally misunderstood – value against the more proper term “mountaineering.”

“Can you imagine someone referring to Norman Clyde as a ‘peak bagger’?” lamented another friend, not as enthused by the slang. Well, no, of course not, but it’s also difficult to imagine one of the most renowned and prolific of all Sierra Golden Age mountaineers doing any running on his first ascent missions in hobnailed boots while loaded down with cast iron cookware and hardbound tomes of Greek mythology .

And herein lies another truth: regardless of which discipline via which you primarily approach the mountains – trail running or climbing – the call of the wild and high summits is as worthy as any to answer. You may even find yourself addicted and working your way through a list, such as “California’s Highest 100 Peaks.”

There is a summit register on a section of the Sierra Crest visible from Bishop with a prolific run ‘n bagger’s frustrated scrawl at discovering he had not, in fact, summitted his Four Gables objective, but an unnamed peak (12,808 feet) just to the north. Coming across this entry later, another local amended the rant with an arrow and a playful jab: “Baggers can’t be choosers!”

In the case of this feature, however, I did have to choose. Here are five worthy peaks on the lower end of the technical difficulty spectrum to whet your “run ‘n bag” appetite.

Mt. Whitney

“You heading to the top?” queried the man at High Camp flagging me down as I ran past. Pointing skyward after looking at his watch, he appeared incredulous. Well, it was mid-afternoon – not exactly a typical time of day to be nearing the base of the infamous Trail Crest switchbacks outbound.

“We’re missing one from our party. Will you keep an eye out for him?”

After nothing but splendid – and exceedingly rare – solitude to the summit and back, the same man approached me in the deep shade of late evening, his concern replaced with a smile. Their companion had made it back safely after initially descending partway down the John Muir Trail toward Guitar Lake on the west side of the crest, instead of crossing back over Trail Crest to the east, because of confusion as to which side of Whitney they had started from.

I bit my tongue, bid the group goodnight and resumed my race against impending darkness to the trailhead. How could you be standing on the summit staring straight down at Whitney Portal and not remember that most basic of geographic details a mere mile later? Quickly cutting my smug thoughts off before they crossed the pretentious pass, I realized that most people attempting Whitney were likely way out of their element, and if I were to find myself in a similar situation – say, in the heart of New York City’s urban jungle – trying to navigate the unfamiliar, I’d probably end up in the fetal position on a bench sucking my thumb.

Despite all the human things – the mid-winter lottery for day passes and the potential crowds regardless, the summit influencer selfies and cell phone conversations, the literal poop bags on the side of the main trail and the elevated potential to have your day derailed by someone else’s figurative shitshow – Mt. Whitney, at 14,505 feet, the highest point in the lower 48, is still fully capable of evoking that crossroads feeling where the trappings of civilization fall away to wilderness.

When alpenglow hits the serrated crest of the Whitney Group at sunrise, and the Sierra’s front teeth are lined with gold, you’ll know what Delta blues icon Robert Johnson didn’t: the mountains can also have a mortgage on your body and a lien on your soul.

The Standard Trail Out & Back:

Distance/Vert: 21.5 miles/7,700 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 8,345 feet/14,505 feet

Trailhead: Whitney Portal

Cliff Notes Beta: Day Use Wilderness Permit required beyond Lone Pine Lake. Class 1 – yet very technical and rocky in stretches – on a marvelous ribbon of trail engineering. Year-round potential for traction device-necessitating ice and snow in a cliff band on the Trail Crest switchbacks.

Map: Tom Harrison Maps – Mt. Whitney Zone

The Mountaineers Route Loop:

Distance/Vert: 16.25 miles/6,900 feet

Cliff Notes Beta: Counterclockwise is most sensible so you can primarily hike the ascent and run the main trail down. The North Fork Lone Pine Creek drainage has a mostly well-established use trail to Iceberg Lake, but it is rugged and steep. Take route-finding care through the Ebersbacher Ledges, remember to hook left before getting to Upper Boy Scout Lake and know that when the chute above Iceberg is filled with ice/snow, it is the real mountaineering deal. Technically considered a third-class route it really depends on chute conditions and how you access the summit plateau after exiting the chute. The further west you traverse, the easier it gets.

The Mt. Whitney 50K:

Distance/Vert: 30.25 miles (but we round up in the mountains)/10,050 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 5,900 feet/14,505 feet

Trailhead: Whitney National Recreation Trail in Lone Pine Campground

Cliff Notes Beta: A local runner once commented, “Only you: ‘Imma make Mt. Whitney an even harder run.’” Here’s betting I’m not the only one. Besides, why let 4+ extra miles of single track languish in the beautiful lower reaches of Lone Pine Creek?

Map: Tom Harrison Maps – Mt. Whitney High Country and/or Mt. Whitney Zone

White Mountain Peak

Approaching from the south, the summit massif of White Mountain Peak appears as the dark metavolcanic prow of a great vessel of mountains barreling west toward the Sierra through a sea of Owens Valley desert sagebrush. At 14,252 feet, the roof of the Basin and Range geographic province is also the surprising third highest peak in California. Although benign in appearance, White Mountain Peak has gotten me ensnared in more epics than any peak I’ve run ‘n bagged in the Sierra.

In early 2009, some basic map math led me to the realization that it was exactly 100k from the 4,000-foot valley floor at Laws Railroad Museum to the summit and back via Silver Canyon and White Mountain dirt roads. The siren song of a standard ultrarunning distance combined with a prominent peak led inexorably to the poor decision of giving it a fidgety first go during a relentless and rare cycle of early June squall-type diurnal storms.

Taunting pockets of blue sky over the summit surrounded by towering walls of cumulus closed ranks with whiteout conditions within minutes of signing the register. Disorientation set in on the descent, and after several hours of anxiety-riddled searching for the road, I chanced upon a calming herd of desert bighorns, regrouped, found my graded gravel lifeline and made it out to the University of California Barcroft Research Station Quonset hut at 12,470 feet by late evening.

Exhausted, and facing a marathon back down in the dark, instead I ended up luxuriating in a hot shower, enjoying a multi-course meal in the company of a few student researchers and nestling into a cozy bunkbed snooze, before finishing what I had started on a full belly and fresh legs the next morning. The friendly caretaker had cornered me before I could sheepishly exit the hut with my self-reliant pride intact.

I did not escape, either, without having to make a call to cancel a first date. Unfazed by my explanation, I got another chance and –15 years later – we’re still together. Now that’s the good kind of epic.

Standard Barcroft Gate Out & Back:

Distance/Vert: 15.4 miles/3,475 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 11,675 feet /14,252 feet

Trailhead: Barcroft Gate on White Mountain Road

Cliff Notes Beta: If the wide, graded gravelly rock road plowed into the landscape doesn’t excite you, the views certainly will. As straightforward as it gets. Follow the road to the summit, passing Barcroft Research Station 2 miles in. No reliable surface water on route.

Map: Sierra Maps – White Moutains

The White Mtn. Peak 100K:

Distance/Vert: 64.75 miles/14,050 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 4,100 feet/14,252 feet

Trailhead: Laws Museum on Silver Canyon Road

Cliff Notes Beta: Again, as straightforward as it gets. Two dirt roads (Silver Canyon + White Mountain) and one left turn. It’s 11.25 miles and 6,200 feet vert to road junctions on crest. Last guaranteed water source is at 7,000 feet where the road peels left away from Silver Creek to begin sharp ascent. To make it exactly 100k, drive 1.4 miles beyond museum and start at a nondescript roadside location.

The West Ridge via South Branch:

Distance/Vert: 19.5 miles/10,525 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 4,550 feet/14,252 feet

Trailhead: Hwy 6/White Mountain Ranch

Road junction

Cliff Notes Beta: For alternate higher start at 5,300 feet, drive 2.5 miles (4WD likely required) up White Mountain Ranch Road and start at base of steep radio antennas road. This is largely a second-class cross-country route (with some avoidable third class – by dropping off ridgeline proper to the north – on a false summit) with relentless elevation gain (think three VKs in a row). No water on route. More hiking than running unless you are a true mountain goat. Don’t be tempted by the North Branch (the two branches merge at 11,500 feet forming Jeffrey Mine Canyon with the famous Champion Sparkplug Mine) unless you enjoy bushwacking on all fours only to run into third-class rock outcrops, repeatedly.

Mt. Agassiz

This northernmost, and easiest to ascend, summit in the otherwise real deal mountaineering arc of the Palisades – the greatest concentration of 14’ers in the Sierra – has always been, to my mind, the crème de la crème of run ‘n bag peaks. Sitting at the head of the South Fork of Bishop Creek drainage and flanking Bishop Pass, it is lofty (13,899 feet), straightforward, combines exquisite singletrack slinking through a charming chain of lakes with solid, non-technical rock scrambling from the pass (and a magnifique glissade if you hit the snow conditions right) and commands exceptional, unobstructed views in all directions.

If I had any reason to question the allure of this peak, coming across its inclusion in Peter Croft’s guidebook The Good, The Great, and The Awesome—a class 2 walk-up amidst a host of the author’s favorite Eastern Sierra technical climbs—closed the case. In 1987, Peter vaulted to the pioneering forefront of the vertical world by linking up free solos of The Rostrum and Astroman, two legendary routes on Yosemite Valley big walls that had only recently transitioned from aid to free climbing styles—a leap forward in boundary-pushing equivalent to Alex Honnold’s free solo of Half Dome’s Regular Northwest Face route in 2008.

In reliving the memories on Honnold’s first Climbing Gold podcast episode in 2021, Croft casually tells of taking his rock shoes off to sit on a ledge partway up the vertical granite world of Washington Column’s Astroman because the experience is going by too quickly and he wants to soak in the views and savor the feeling of not having the slightest desire to be anywhere else.

I highly recommend doing the same on the summit of Agassiz.

Class 2 Route:

Distance/Vert: 12.5 miles/4,725 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 9,785 feet/13,899 feet

Trailhead: Bishop Pass/South Lake

Cliff Notes Beta: In between the top of the final steep switchbacks and the actual pass, leave the trail, cutting left cross-country towards the what-should-be obvious main gulley (often with the only lingering snowfield at its base) and wind your way up through ledges and talus before arcing left along the summit ridge to the top.

Map: Tom Harrison Maps – Bishop Pass

Winuba (aka Mt. Tom)

If ever there was an example of the oftentimes swing-and-a-miss style of European naming conventions – principally, the ego-driven need to name things after oneself – in the mountains, one need look no further than the beautifully geometric monolith of a mountain dominating the Bishop skyline to the west. It’s impossibly long and low-angle north ridgeline combines with a much shorter, and steeper, southerly drop-off into the Horton Creek drainage to form an acute triangle framing an inspirational backdrop to life in the northern Owens Valley. Standing at “only” 13,658 feet, Winuba’s position significantly east of the main Sierra Crest makes it feel much taller – imposing itself on the subconscious whether one’s eyes are drawn to it with reverential intention or not.

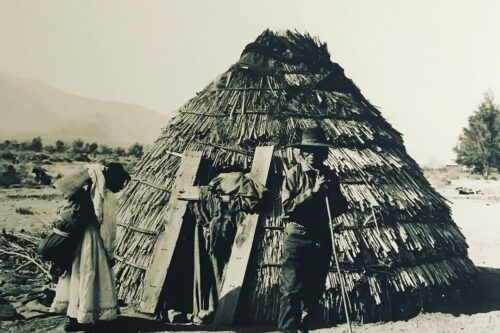

The Paiute name, Winuba, meaning “standing tall,” evokes a deep sense of connection with the land, whereas Tom simply references Thomas Clark, a resident of the nearby, and short-lived, 1860s mining camp of Owensville, considered to be the first White settler to climb the peak.

Standing tall on the summit, after a hard-earned run and scramble to the deified views, there’s really no question as to which moniker best befits a cathedral readymade for heightened spiritual commune with the natural world.

Horton Creek/Hanging Valley Route from The Buttermilks:

Distance/Vert: 22 miles/7,300 feet

Start/Summit Elevation: 6,425 feet/13,658 feet

Trailhead: Buttermilk Road just up from main bouldering area parking (alternatively, you can drive as far as your vehicle and road conditions will allow – upwards of 3 miles – to the signed trailhead at 8,000 feet to shorten the route)

Cliff Notes Beta: Just before reaching Lower Horton Lake (last water), peel right (easy to miss) up a heavily eroded, steep mining road to the brief reprieve of the Hanging Valley. From the ruins of the Tungstar Mine at the road’s end, choose your adventure up steep and loose chutes to the summit. This is admittedly heinous Sierra choss, but the views are so worth it and the run back down from the mine is a bombtrack blast!

Map: Tom Harrison Maps – Mono Divide High Country

Boundary + Montgomery Peaks

The soft contours of the White Mountains that extend, largely uninterrupted and steadily rising from south to north, end abruptly at a chasm known as The Jumpoff. This separates the gently rolling 13,000-foot desert tundra terrain of the Pellisier Flats from the sharper angles of the twin triangular peaks of Boundary and Montgomery. Boundary – depending on parameters of prominence used – is the highest point in Nevada, with the California state line running through the saddle separating the two summits.

In the summer of 2004, while on the ridgeline 1,000 feet below the summit, I turned around to see where my run ‘n bag companion was just in time to witness a lightning bolt striking one of the pines far below us in Trail Canyon. Before I had a chance to yell the obvious – time to bail – I enjoyed a balcony view of someone much more into the ‘bag’ than the ‘run’ take off like Usain Bolt down the loose scree.

Choose your forecast window more wisely than we did, and you’ll have a greater chance of seeing herds of desert bighorn and wild Mustang versus Greek gods of weather on the way to the summit—but you might miss out on the elusive rainbow.

Queen Canyon Saddle Route – Long (Standard)

Distance/Vert: 24 miles/8,000 feet (9.5 miles/4,550 feet)

Start/Summit Elevations: 6,300 feet (9,750 feet)/13,147 feet + 13,441 feet

Trailhead: Junction of Hwy 6 + Forest Service Rd # 1N14 (Queen Canyon Saddle proper)

Cliff Notes Beta: Running, instead of driving, the access road to Queen Canyon Saddle is a wonderful, moderate-grade addition to the short and steep standard route that begins at the saddle; only drawback is there is no water, unless you can bushwack your way into the creek that briefly surfaces low in the canyon. The amazing singletrack becomes braided and tedious on the upper flanks of Boundary’s very loose scree and talus. The three-quarter-mile traverse between the peaks is equally tedious due to the need to side-slope to the east off the ridge proper to avoid more involved rock outcrops.

Map: Sierra Maps – White Mountains

Written by:

Jeff Kozak

"Jeff Kozak discovered the magic of the Eastern Sierra as a kid at the family summer cabin, the transformative power of running in high school cross country, and combined the two passions with a love for adventure on foot that has led to three decades of racing ultras, and roaming far and wide in the Eastern Sierra region. His forthcoming guidebook, "Eastern Sierra Trail & Adventure Running: Come for the Beta, Stay for the Stories, Head out Inspired!" is born of that lifelong love. He can be reached at jeff.kozak.1974@gmail.com."